Why Artemis?

All about our name change, our logo, and why we chose the ancient goddess.

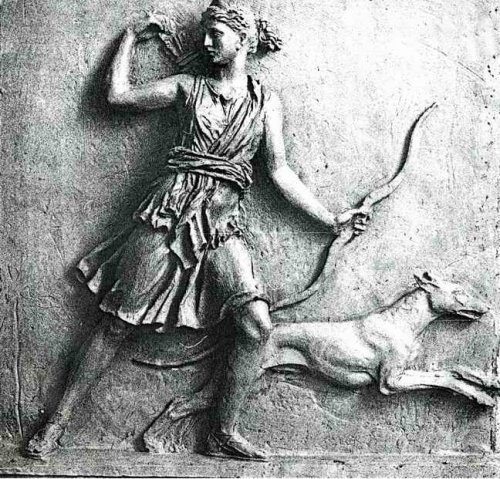

Artemis depicted on a frieze, with her hunting bow and hound.

I’ve had the image above in my phone since 2016, when I first started thinking about what I would call my business if it hadn’t already been named. I love this depiction of the goddess especially, for her movement, her confidence, her ease of skill with her bow and her hound. She is in her element, of the elements. She looks, to me, like a woman whose objective is clear and consuming, absorbed in her work and at the height of her power.

As we considered our name change, I researched Artemis more, and she began showing up in daily life. NASA named their “first woman on the moon” mission Artemis, leaning on her association with the Moon and her sisterhood to Apollo, the sun god. My partner Nelson’s company also named a project Artemis. And as we started thinking about having children, Artemis appeared as the goddess of childbirth. The more I learned about her, the more I felt she embodied what I wanted to do with our farm, and my life.

Briefly, in Greek mythology, Artemis is the goddess of the hunt, the wilderness, wild animals, the Moon, and chastity, and also among the primary goddesses of childbirth and midwifery. She is the child of Zeus and Leto, and Apollo’s twin sister, born first, who then helped her mother deliver her twin. Her symbols are the bow and arrow, the Moon, and the stag or the doe. Her flower is red amaranth, Greek amarantos, meaning unfading. She is sometimes depicted carrying a torch: a beacon.

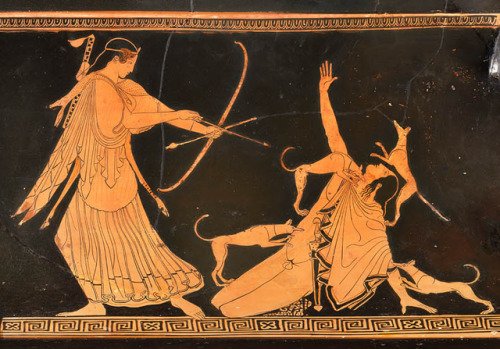

Artemis and Actaeon. Actaeon, her hunting companion, saw the goddess nude while she was bathing. In punishment, she transformed him into a stag, and he was devoured by his own hounds.

Artemis means many things to many women. Some of these feel most true to me: Artemis is the “personification of an independent feminine spirit,” a woman who can “seek her own goals on terrain of her own choosing”. Artemis is the symbol of unencumbered, undiluted femininity, “defined neither by relationship to a lover, nor to a child, nor with father, nor to husband.” She is wholly and unapologetically herself. Catriona Glazebrook writes that “Artemis’ earthy-spiritual base is where she derives much of her strength, her endurance and her power. It is also the wellspring of her great compassion and love”. (Notes 1, 2, & 3)

What do all these symbols and associations have to do with one another, and what do they mean in sum? What does hunting have to do with childbirth, or the deer to do with the Moon? What is the underlying truth that Artemis represents? I first began to understand how appropriate and important Artemis was, for me, when I read the following, in a beautiful and empowering book about the journey of childbirth:

Artemis is the yin to Apollo's yang. Artemis is the huntress in the wilderness, friend and hunter of wild animals. Artemis favors instinct, impulse, and natural order… she is the wild to Apollo's cultured and civilized order. Artemis lives in the wilderness while her twin lives within cities and towns…Where Apollo is at home in the sky, Artemis lives close to the earth and is of the earth. If he is order, she is chaos. Apollo is the day, and Artemis the night…Where he is linear, orderly, and directive, she is unpredictable and hidden. He is knowable; she is mysterious. (4)

Artemis and her symbol, the stag.

I might add that where he is constant and straightforward, she is change: cyclical and volatile. The moon, after all, changes every day, and pulls on the water of our bodies, and our bodies of water, in ways we can’t always predict, and definitely cannot alter. In the book on childbirth, we are encouraged to accept the Artemisian nature of birth; that is, to accept that we will not control the experience, and that when we can submit to it and allow ourselves to enter our elemental and wild animal nature, we can release ourselves from expectation, desire, and suffering (at least of the emotional variety). In an article on homebirth, Sydney Amara Morris writes that, in childbirth, women can glimpse the essential nature of the universe, because the process of birth and creation is inextricably tied to the possibility of death. (5) Perhaps that is why Artemis is both the hunter and the protector of the wilderness and wild animals: death is part of life is part of death, and that is the nature of earthly life for women.

These are concepts that I am very, very uncomfortable with. I am not a lover of chaos or change, especially the kind I can’t control. My mother and my partner will tell you that, if I make a plan and it doesn’t go the way I envision, I more or less throw a temper tantrum. But in working with plants, in the soil, with the weather and the wind and rain, I have come to know how very little I know; how very little I can control; how much I really am at the mercy of what Artemis represents. To work in nature is to accept the uncertainty of every act: to accept failure, death, and the mess of birth.

I’ve also come to think that beauty and joy are very much functions of chaos and the unknown: much of what is beautiful about flowers is the sheer wonder of their existence, the delightful and astonishing fact that the world on its own could make something so perfect, so shimmering and architectural and seemingly designed. Chaos is generative. Chaos is the great black pool of matter and energy and existence out of which, somehow, without human knowledge or intervention, beauty grows. As the old book says:

And the earth was without form, and void; and darkness was upon the face of the deep. And the Spirit of God moved upon the face of the waters. (6)

The deep, the waters: the formless chaos that existed before creation. Artemis means we have to revere that which we don’t know or understand, for it is certainly the foundation of everything we are. If the creator God is the Father, the formless unknown is our Mother.

But what does this all have to do with farming? For me, it means that there are processes at work in the soil, in the air, in the borders of the farm, that I do not and cannot ever understand. It means that in honoring the natural world, I must let that unknown inside and I must protect it. I must rewild my farm in that same way I rewild my mind, away from capitalism and patriarchy and toward community and communality. I must accept, too, that death is generative of life, that my dying plants provide nourishment for next season’s flowers, that the death and birth of bacteria, fungi, nematodes, and earthworms, even the aphids that feed beneficial insects that feed beneficial birds, are the driving engine of my farm’s health — and therefore of my family, community, and the earth’s health. I must disturb this unknown network, these invisible but essential processes, as little as I can; I must tread lightly and allow them to do their work without me.

Fertility Print, by the artist Daren Thomas Magee of Real Fun, Wow! We gained a lot of inspiration from Magee’s work, because of how it blends the earthly with the spiritual. Go buy his art.

On the farm, in practice, this means several things:

We don’t turn the soil: therefore, we protect the homes of the soil organisms we rely on;

We cultivate bacteria, fungi, nematodes, arthropods, and actinomycetes by using natural biologically active amendments;

We encourage birds and pollinators by growing and preserving native plants and perennial bushy shrubs for habitat;

We accept that nutrient deficiencies and pest infestations are symptoms of an imbalanced or disturbed system, so we seek balance and healing rather than revenge or annihilation.

In psychoanalysis and literary criticism, The Real is a concept referring to the things that can’t be expressed in words, and which are lost when we learn to represent them with language. I must accept that beauty and goodness arise not from my well-laid plans, but from the spark of the Real that lights my plans on fire.

In naming the farm Artemis, I hope to remind myself that the things we don’t understand, or are outside our control, should be revered, cherished, and nourished. I hope to move forward into our new piece of land, our new relationships and community, by embracing the glorious sparkling chaos of it all. I hope the new name holds some meaning for you, too, and that you’ll find pieces of Artemis on our farm, through the wonder and untamed brilliance of flowers, and the cycle of the moon and the seasons, and the simple pleasure of just letting go and letting yourself be part of the wild, ineffable world.

And yes, when we make fun of ourselves for our pretentious Greek goddess name, we call it Fartemis. 💨

About the Design

The moon, of course, is the moon.

On the symbol:

We chose two of Artemis’s symbols for the logo: the moon and the deer (or at least, its antler). I wanted something different, and not a flower, because the real purpose of Artemis Flower Farm is not flowers — it’s health: of our land, our bodies, our communities. It’s about making room for the birds and frogs and butterflies and bobcats.

The antler also mirrors the branching networks of trees and roots whose functions are so central to the health of our soil. An antler is an organic object, growing and creating its form in response to complex cues we don’t understand, or need to, like a shell . Like a flower, it is wonderful, in that it makes us experience wonder. Antlers are cyclical, too, growing and falling off every year, so they can be a reminder to us of impermanence: that perhaps impermanence is an essential aspect of beauty.

The moon, of course, is the moon, growing and growing like a pregnant belly, waning away as we do in death, tugging at our bodies and our seas with its subtle gravity. I love how the sharpness of the antler cuts across the round and satisfying shape of the apricot moon.

On the colors:

We chose more vibrant colors than our previous brand: warm, welcoming colors like coral, peach, and pool-blue. They are colors that help us feel both comforted and invigorated, invoking confidence and comfort. In the past, I’ve been hesitant to make my brand too strong, too bright, or too bold, because I wasn’t confident in my abilities as a grower or a designer. I told myself that the washed-out colors were elegant, or subtle, or calming, but really I was just hiding. I’m done hiding, and I’m ready to step into my power by sharing it with the world.

On the type:

Nelson, my incredible partner in business and life, is a talented designer, and prevailed upon me to choose the beautiful typeface we ended up with for our logo, over a more staid and shrinking font that was my natural tendency. We needed something powerful but welcoming, sharp but rounded, something, like Artemis, unapologetically itself. He found our font, called Epicene, at the Klim Type Foundry.

Just visit their home page and see Epicene’s stunning visual introduction, a work of art in itself, like the typeface. Nelson and I are both big typeface or font nerds (in college I wrote a 15-page paper about the Baskerville typeface and its expression of the cultural change between the Enlightenment and the new Romanticism of the mid-18th century), and we absolutely adored the amount of work and effort that went into this typeface, as evidenced by the deep research the designer did to make it come to life. Kris Sowersby thinks of his typeface as a mediation between two different typefaces by two accomplished Dutch designers of the 18th century: Rosart and Fleischmann. (As far as Nelson & I are concerned, the fact they were Dutch was a big bonus).

I am obsessed with these lines from Sowersby’s blog about Epicene (which you should definitely take a look at):

Describing things as “masculine” or “feminine” in design and typography is historically and culturally loaded. Language is powerful, typography makes language concrete. Language has a shared meaning and heritage … When they write “delicate and light” is feminine, “strong and bold” is masculine, they’re really saying “women are weak, men are strong”. It’s that simple. This language is corrupt and bankrupt in today’s society. Gender shouldn’t be used as a metaphor when better, simpler language is available … To be epicene means to lack gender distinction, to have aspects of both or neither… [Epicene] is an experiment in modernising Baroque letterforms without muzzling their ornamental idiosyncrasy nor falling into the trap of gender codifications.

Sowersby summarizes his typeface thus: “Typographically, Epicene’s exaggerated details add rigour at small sizes and vigour at large sizes. Culturally, Epicene says one thing: typefaces have no gender.”(7)

Maybe goddesses don’t, either.

I loved, loved, loved this deep understanding of design and signification, and of course I felt immediately that Epicene would be the right typeface to represent the ideas of Artemis, both the goddess and the flower farm. As a flower farmer, I often find myself crossed between the “masculine” traits my work requires, like toughness, stamina, perseverance, and future visioning, and the “feminine” qualities of what we produce: floral, delicate, beautiful, fragrant, and ephemeral. Artemis holds these juxtapositions, too, in both her changeability and her fierceness, both nurturing and ruthless: a femininity that is free from definition based solely on comparison to masculinity.

I hope you find something to inspire you in this treatise, and that Artemis can be your beacon and guide to freedom—freedom from any kind of definition except that which you choose for yourself.

With great love and gratitude,

—Helen

Notes

(1) Bolen, Jean Shinoda. Goddesses in Everywoman: A New Psychology of Women. New York: Harper Perennial, 1985.

(2) Woogler, Jennifer Barker. The Goddess Within: A Guide To The, Eternal Myths That Shape Women's Lives. New York: Ballantine Books, 1989, p. 11.

(3) Glazebrook, Catriona. “Artemis”. The Trumpeter: Journal of Ecosophy, Vol. 13, No. 1 (1996). Accessed at: http://trumpeter.athabascau.ca/index.php/trumpet/article/view/273/408

(4) Bushnell, Britta, Ph.D. Transformed by Birth: Cultivating Openness, Resilience, and Strength for the Life Changing Journey from Pregnancy to Parenthood. Louisville, Colorado: Sounds True, 2020.

(5) Morris, Sydney Amara. “Homebirth: The Sacred Act of Creation”. In Sacred Dimensions Of Women’s Experience. Gray, Elizabeth Dodson (Editor). Wellesley, Massachusetts: Freidman Feminist Press Collection, 1988.

(6) King James Bible, Genesis 1:2.

(7) Sowersby, Kris. “Epicene design information”, September 2021. https://klim.co.nz/blog/epicene-design-information.